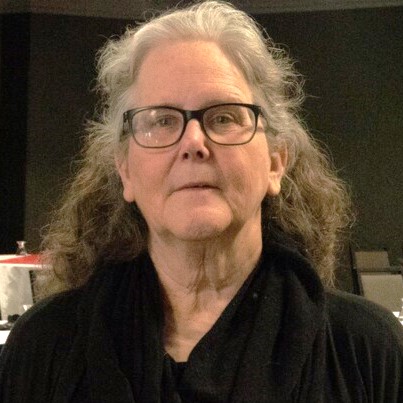

Jennifer Côté (photo at right) wanted real milk. But as a vegan who’s concerned about animal welfare and the environment, she wanted real milk without the dairy cow.

Jennifer Côté (photo at right) wanted real milk. But as a vegan who’s concerned about animal welfare and the environment, she wanted real milk without the dairy cow.

So she co-founded Montreal-based Opalia and is in the fifth year of her journey as a startup founder – learning as she goes.

Founded in 2020, Opalia’s mission is to develop real milk and milk ingredients, from cells instead of cows, to produce more sustainable, ethical and nutritious dairy products.

“Personally, I was looking for better-functioning dairy alternatives,” Côté said in an interview.

She and Opalia’s co-founder and chief technology officer, Lucas House, knew producing real milk without the cow and the associated animal welfare concerns and environmental impacts was a big problem that required a big solution.

“So with our personal motivation and just our desire to make the change, we thought that we were positioned to be the right people to build this,” Côté said.

There are plant-based alternatives to milk on the market. They’re good enough to put in coffee and on cereal, Côté thinks. But for making products like cheese, ice cream or butter, the existing alternatives fall short when it comes to taste, consistency, mouthfeel and other important qualities in what Côté calls “our personal relationship” with food.

Also, “we’re not seeing as fast an adoption rate [of plant-based products] as we would like to see,” she said. “A lot of people are still dependent on real dairy, whether it’s for taste or just because of their culture.”

Côté and House conducted their own foundational research on the idea of trying to make milk using mammary gland (udder) cells obtained from dairy cows. They found a scientific paper by a University of Toronto (U of T) engineering student that described something very similar to what they wanted to do.

They reached out to her, which resulted in a group of U of T students doing the proof-of-concept for Côté’s and House’s idea.

Although the engineering student didn’t join Opalia’s team, “she really pushed us to hire the team that could do these [cell] manipulations,” Côté said. “And then we were able to attract some funding to further build the team and that’s where the project got started.”

The first challenge Opalia faced was finding wet laboratory space where the company could conduct its cell-manipulation experiments. Lack of wet lab space is a long-standing problem in Canada’s biotech/life sciences industry.

Opalia managed to find sufficient wet lab space shared by startups at the District 3 innovation incubator in Montreal. “Without that, it would have been impossible to start,” Côté said.

The other big challenge – which almost all Canadian “hard tech” startups face – was securing sufficient early-stage investment to do the R&D required to develop a novel technology.

At the beginning, the idea of making real milk without cows sounded intriguing and attracted initial funding to Opalia, Côté said. “Milk without cows is a bit of a funky idea. But when you think about it, I think a lot of people are interested in supporting it.”

However, attracting funding now, as Opalia works to scale up its technology, “is “becoming more and more of a challenge,” she said.

Securing early and ongoing investment is especially challenging for startup biotech companies because they go so long without earning revenue. The R&D development process is long and costly, requiring capital-intensive equipment and facilities.

“That’s what makes it hard, especially in Canada,” Côté said. “I don’t think we’re used to that kind of investment model where the company needs capital to start, not to grow or to launch their product to market.”

Benefits of Opalia’s cell-based technology

Opalia uses a four-step technology for making milk from bovine mammary gland cells:

- Epithelial cells (found in skin, blood vessels and organs) are isolated from the mammary gland of the cow.

- These cells are fed a mix of sugars, salts and amino acids and are grown inside a bioreactor that replicates the in-vivo environment of the cow udder.

- Lactation (milk production) is initiated in the cells inside the bioreactor using Opalia’s proprietary process.

- Milk is harvested from the bioreactor and transformed into dairy products.

“Our process is a continuous process,” Côté notes. “That’s really competitive in the industry, especially when you’re wanting to reduce the costs.”

Opalia’s cell-derived milk has multiple benefits compared with milk from dairy cows, she said.

The milk is animal-free, containing no antibiotics or hormones. Opalia’s production process is sterile, eliminating concerns about bacterial contamination or cows having a flu virus, including H5N1 (avian flu virus) that has infected cattle in the U.S.

Opalia’s process uses less land and water and also eliminates methane emissions from dairy cattle, reducing these emissions by up to 95 percent.

This is significant, considering studies show a lactating dairy cow produces about 400 grams of methane on average each day – equivalent to the greenhouse gas emissions from a mid-sized vehicle driven 20,000 kilometres in one year.

A dairy farm with 100 cows emits an average of about 11,500 kilograms of methane during the winter alone, the equivalent emissions of about 74 gasoline cars being driven for a year. Taking into account the more than 9,000 dairy farms across Canada, that’s a lot of methane.

Moreover, methane is a potent greenhouse gas that has a global warming impact 25 to 27 times greater than that of carbon dioxide.

Côté said another big benefit is Opalia’s animal-free milk contains all of the functional components of conventional dairy cow milk, including the six main proteins (two whey proteins and four casein proteins), milk fats and milk sugars. This enables a wide range of applications in making milk-derived products.

“We have full control over what the cell is able to produce, so we can easily tweak what the cell produces to have a lactose-free milk [or] removing the A2 protein which is allergenic.”

“We also can modify the fat content or protein content,” she added. “So that makes it easier to build up customized dairy products.”

Toronto-headquartered CULT Food Science Corp., which invested US$250,000 in Opalia in 2022, pointed out in a news release that Opalia also has successfully replaced fetal bovine serum from its process, reducing the cost and risk of manufacturing cell-based milk.

Opalia is the first Canadian company to produce cow milk from mammary cells, CULT Food Science said.

The global dairy alternatives market is projected to grow from US$22.25 billion in 2021 to US$53.97 billion in 2028.

Opalia has international competitors working on similar cell-based technology, including Senara in Germany, Brown Foods in the U.S., and Wilk in Israel.

Côté welcomes the competition. “It really highlights the need for this technology. And also, we’re not going to do it alone. It’s impossible to tackle this challenge alone.”

“So we really like to see other companies making progress with this technology and getting more and more people interested.”

Public funding has been crucial for Opalia

Opalia has received a lot of support from innovation hubs like District 3 in Montreal, MaRS in Toronto and others, Côté said. This support includes capital, networking and mentorship from seasoned startup founders.

“As a first-time founder, there’s a lot I didn’t know. There’s a lot I still don’t know,” she said. “So it’s useful to have people around us that have gone through it or know a specific part of the startup journey. That really helps.”

In March 2024, Opalia attracted $2 million in a funding round led by Netherlands-based Hoogwegt Group, the world’s largest independent supplier of dairy products and ingredients. Other investors included Ahimsa Foundation, Box One Ventures, Cycle Momentum, Kale United, and the Québec government, through its Impulsion PME program managed by Investissement Québec

Opalia also has attracted public funding and support from several sources, including Natural Products Canada, Sustainable Development Technology Canada, the National Research Council-Industrial Assistance Research Program, Mitacs and others.

There are so many great funding programs that support R&D, especially in the cleantech sector,” Côté said. “We’ve been very fortunate.”

Government funding is the key to mitigating the risk of securing private investment in innovative biotech technology that’s going to take several years to achieve a return on investment, she said. “We use a lot of that funding to prove the milestones that are crucial for investors to know that we’re the right team to tackle this challenge.”

Canada’s innovation ecosystem is good at supporting startups to get their idea started, Côté said. However, she added, “I think what’s missing is really that gap between early idea validation and commercialization, especially in cleantech.”

Developing hard tech requires investing in equipment and facilities, Côté pointed out. “It’s not software. It has to be physical and that comes with a lot of capital.”

To scale up and validate the technology in a pilot production project, “there really has to be a partner that’s wanting to join you and support you,” she said.

Creating a database where tech startups could find and connect with partners willing to collaborate would be vey helpful in putting all the pieces together to get to commercial production, Côté said.

Likewise, creating a national bioeconomy strategy could help ensure financial support throughout the entire startup journey. This would enable companies to scale up by proving technology-development milestones and moving through a timeline of funding.

“We just need more support throughout all the different stages,” Côté said. “Especially when we’re competing against the United States which has so much more funding available for companies.”

Opalia is currently fundraising and will need a partner with a bioreactor facility to move to a pilot production project. “We’re open to any partners to collaborate, to do R&D, to help us get to market,” Côté said.

Lessons learned as a startup founder

Because Opalia’s products are classified as “novel food,” the company also will require regulatory approval from Health Canada and the Food Inspection Agency before launching products into the market.

Côté hopes to start research trials of products with customers next year and then launch Opalia’s first products into the market a year or two after that.

The company’s first product will likely be a cheese, a yoghurt or a butter, rather than milk, mainly to showcase the versatility and functionality of cell-based milk and build a customer base, she said.

Customers initially will have to pay more for Opalia’s products compared with conventional dairy products, given the company’s small-scale production process, which is expensive. However, Côté points out that the production itself can occur at the same place the milk products are made, eliminating the cost – and associated emissions – of transporting dairy cow milk from farms to product production facilities.

“Reducing a lot of these steps will eventually lead to lower costs, but probably at a larger scale,” she said.

Côté said one of the biggest things she has learned as a startup founder is the necessity of teamwork.

“It’s a really, really complex thing that we’re building and doing that alone – not only in my team but also with the external partners advisors –and the network you build throughout all of that is really key.”

For example, some of the people Côté and her team first met when Opalia was founded in 2020 are now investing after five years of following the company’s progress. “So it’s really about all of those connections that make us stronger and more resilient through all of this.”

When asked what characteristics an entrepreneur and startup founder needs, Côté replied: “A high tolerance to stress,” and then laughed. “Being resilient. Persistent. Kind of stubborn.”

She knew her journey with Opalia would be a long one, because all of the R&D required for the technology didn’t exist. She and her co-founder – and now a team of six including them – had to perform all this foundational R&D themselves.

Said Côté: “You have to be intrinsically motivated because if you’re not, it’s a very difficult journey.”

R$

| Organizations: | Opalia |

| People: | Jennifer Cote |

| Topics: | cell-based milk products and producing real milk using cells |

Events For Leaders in

Science, Tech, Innovation, and Policy

Discuss and learn from those in the know at our virtual and in-person events.

See Upcoming Events

You have 0 free articles remaining.

Don't miss out - start your free trial today.

Start your FREE trial Already a member? Log in

By using this website, you agree to our use of cookies. We use cookies to provide you with a great experience and to help our website run effectively in accordance with our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

.jpg)